Authors:

Kellina Lupas, PhD, Clinical Director of the Center for ADHD, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Stephen P. Becker, PhD, Co-Director of the Center for ADHD, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common mental health condition in childhood, affecting approximately one in every nine children (Danielson et al., 2022). Schools are the primary source of mental health support for many families – and ADHD is no exception. Insufficiently preparing teachers for working with students with ADHD – and myths about the best ways to support students with ADHD in the classroom – are common. To best support students with ADHD in the school setting, it is important to first understand how schools support student behavior and attention generally (e.g., Sugai & Horner, 2009), and then clarify what school supports effectively improve the day-to-day functioning of children with ADHD (Fabiano & Pyle, 2019).

Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS)

Symptoms consistent with a modern diagnosis of ADHD have been documented in educational settings since the early 1800’s (Thome & Jacobs, 2004). In fact, school-related impairment is a core feature of the disorder (e.g., inability to finish classwork, poor organization, interrupting behavior), and gathering input from teachers is considered a critical component of diagnosis. School supports for children with disabilities like ADHD have often been relegated to more exclusive, special education settings, under laws like the 1975 “Education for all Handicapped Children (EHA)” (later re-born as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act [IDEA]). However, over the past several decades, there has been a broad movement across mental health and education to promote inclusivity and reduce exclusive education practices (Mandlawitz, 2016). As a result, there has been steady momentum within schools to find ways to support students with disabilities in general education settings. This “inclusive education” approach emphasizes that many interventions targeting academics and behavior can be delivered well before a child is determined to need an exclusive, separate education setting (like a small classroom). It also highlights how all students can benefit from good instruction and classroom behavior management – and that we should help all educators put these in place, not just educators in special education. Terms for these types of systems include response-to-intervention (RTI), positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS), and multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS).

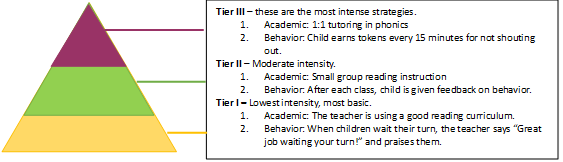

Modern MTSS typically include three “tiers” of strategies, as shown in the Figure. Tier I includes the most basic or foundational strategies that are likely beneficial to all students (e.g., a good reading curriculum, Class Dojo), Tier II being more moderate intensity supports for a smaller group of students who aren’t showing growth with Tier I alone (e.g., small group reading instruction, social skills group), and Tier III being the highest intensity, most individualized supports (e.g., 1 on 1 phonics instruction five times a week, individualized behavior plan). Movement through the tiers (e.g., from Tier I to Tier II) is usually decided by a school-based team that collects and reviews academic or behavioral data. For instance, if your child has ever had a fall “benchmark” reading assessment, those are typically used to determine which students are showing below-grade reading skills, and then shift those students from Tier I to Tier II for the next few months. If a child gets to Tier III, and they are still not showing growth, the school team typically places a referral for a special education evaluation (for a 504 Plan or an Individualized Education Program [IEP]). This pathway should highlight that schools are trying to make exclusive educational settings (like those that come with special education) the very last approach, after they have tried everything else!

Tiered Supports for Students with ADHD

Knowing that most schools have adopted a multi-tiered approach to support that emphasizes intervention well before the special education evaluation, parents and educators can best support students with ADHD by advocating for evidence-based practices at each tier. Thankfully, there is a wealth of research on effective psychosocial interventions for children (DuPaul & Stoner, 2014; Fabiano et al., 2021), and how these fit into a tiered system (Fabiano & Pyle, 2019; Vujnovic et al., 2014).

Tier I – Foundational Classroom Management

At Tier I, students with ADHD are best supported by positive behavioral classroom management strategies. These include:

- Rules: Children with ADHD benefit from clearly defined, positively stated rules. For instance, “Stay in your seat” is a clear, positively stated rule, rather than “Be good.”

- Labeled Praise: Catching children with ADHD when they are following the rules is a great way to demonstrate that your attention (which is very valuable!) is earned for doing the right thing. Common recommendations for praise are to use a 3 (praise) to 1 (reprimand, redirection, command) ratio. This is tough to meet, but remember that praise does not just need to be given to the student with ADHD – you can spread your comments throughout the class to meet that goal.

- Effective Commands: Children are more likely to follow directions that are clearly stated, and given one at a time. For instance “Please put away your folder,” versus “What should you be doing right now?”

- Transitional Warnings: Children with ADHD can quickly lose a sense of time. It is helpful to give regular external warnings of time (make sure you have their attention before you give the warning). These can include actual clocks, or just statements like “You have ten minutes till we go to lunch.” “You have five minutes till we go to lunch.”

- “Premack Contingencies”: These are “If-then” “First-then” and “When-then” statements, such as “When you complete five more problems, then you can have five minutes of free time to draw.” They put less desirable tasks first, and more desirable tasks later.

- Planned Ignoring: Many minor, irritating behaviors, like humming, complaining, or whining, are attempts at gaining your (often negative) attention. Ignoring these, and instead immediately praising the child when they stop (or engage back in the learning) helps show what earns your attention. Over time, the negative attention seeking behaviors will decrease.

Tier II – Daily Report Cards

The most well-supported, evidence-based Tier II intervention for children with ADHD is the Daily Report Card (Iznardo et al., 2020; Pyle & Fabiano, 2017). Daily Report Cards include a set of individualized behavior goals (e.g., “interrupts fewer than 3 times per class”), which are rated throughout the day (e.g., during math, reading, science), and which result in positive rewards or privileges earned at school or home (e.g., if you receive a “Yes” on at least 70% of your goals today, you can earn 45 minutes extra screentime).

Two excellent resources to help parents and teachers establish a daily report card are Dr. Greg Fabiano’s free Coursera course, “ADHD: Everyday Strategies for Elementary Students” or Dr. Julie Owens’ “Daily Report Card Online” (DRCO) platform.

Tier III – Functional Behavior Analysis and Behavior Intervention Plans

To go beyond classroom management techniques and the daily report card, the next best intensive approach is to conduct a functional behavior analysis (FBA) and pair it with a behavioral intervention plan (BIP). While these are terms most often used in special education for students with IEPs, any student can theoretically receive an FBA and BIP, as these are just terms for a formal process to understand why students are engaging in certain behaviors, and then tailor interventions based on that information. FBAs and BIPs are often conducted by school mental health professionals, like school psychologists, in collaboration with teachers.

Information from FBAs can be directly applied to modifying the Daily Report Card (Vujnovic et al., 2014), for instance:

- Ensuring that prompts for Daily Report Card goals are given immediately following the behavior (making sure implementation has high fidelity)

- Use visual prompts instead of verbal ones to increase child’s ability to track progress (e.g., pom-poms that are removed for each reminder)

- Modifying the criteria for earning a reward (e.g., instead of needing to meet 70% of your goals, you only need to meet 50% – making it more attainable to increase buy-in)

- Increasing the number of times throughout the day that the child has their behavior rated (increase opportunities for feedback)

- Increasing the number of times throughout the day that the child can earn positive reinforcement for meeting their goals (decrease delay to reward)

Data-Based Decision Making

Data are essential for determining if a child is making progress with a tiered approach! Collecting data regularly (ideally daily) helps parents and educators decide if they need to:

- Modify or add an intervention

- Fade out an intervention due to improvement

The good news is that interventions like the Daily Report Card produce their own data. For instance, educators can take the daily percentage of goals met on the Daily Report Card and graph those over time to show progress. Even better, online platforms like the DRCO do this for you – eliminating the need to be a wizard at Excel.

There are no clear standards for making the decisions listed above, but some good rules of thumb are:

- “Flat-lining” without progress: make the goals easier or rewards more frequent

- Child behavior is worsening: ensure the Daily Report Card is being used appropriately, add in opportunities for feedback or reward, ensure rewards are sufficiently motivating

- Disruptive behaviors have decreased (or on-task behaviors increased) by 20%: make the goals harder, reduce feedback, or reduce number of rewards (start to fade out)

Summary

This article highlights that there are highly effective school-based supports that can help students with ADHD complete more of their work, stay organized, and create fewer disruptions. These approaches have the strongest support for children between 6-12 years old (elementary age). For younger children (3-5 years old) or adolescents, we have less support for these approaches, although there is promising evidence for behavioral interventions that emphasize parents and teens engaging in treatment at the same time training organizational, time management, and study skills (e.g., Evans et al., 2011; Sibley et al., 2016).

Additionally, there is strong support for a combination of behavioral approaches, like those described above, and medication management (e.g., stimulant medication) to improve both symptoms and impairment (Connors et al., 2001). As educators do not prescribe or manage medication, this article focuses on psychosocial or behavioral approaches, as these will be the types of strategies most relevant to the school context. However, it is important that parents know that adding on medication is a safe and appropriate intervention step, as schools begin to implement behavioral strategies and track progress (Pelham et al., 2016).

There are notable exceptions from this list of effective supports. We intentionally do not discuss in detail special education plans like 504 Plans or IEPs, or school accommodations like extended time. While these are often the first approaches we think of when envisioning children with disabilities like ADHD in the schools, they often fail to produce significant improvements in functioning (Fabiano et al., 2024). A tiered approach that emphasizes early classroom behavior management shows the largest improvements in impairment – as rated by teachers (Fabiano et al., 2021)! Parents and educators have limited time and energy; advocating for the supports most likely to produce the largest benefits is crucial when we consider the overwhelming number of options available.

References

Conners, C. K., Epstein, J. N., March, J. S., Angold, A., Wells, K. C., Klaric, J., … & Wigal, T. (2001). Multimodal treatment of ADHD in the MTA: An alternative outcome analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(2), 159-167.

Danielson, M. L., Holbrook, J. R., Bitsko, R. H., Newsome, K., Charania, S. N., McCord, R. F., … & Blumberg, S. J. (2022). State-level estimates of the prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and treatment among US children and adolescents, 2016 to 2019. Journal of attention disorders, 26(13), 1685-1697.

DuPaul, G. J., & Stoner, G. (2014). ADHD in the schools: Assessment and intervention strategies. Guilford Publications.

Evans, S. W., Schultz, B. K., DeMars, C. E., & Davis, H. (2011). Effectiveness of the challenging horizons after-school program for young adolescents with ADHD. Behavior therapy, 42(3), 462-474.

Fabiano, G. A., Lupas, K., Merrill, B. M., Schatz, N. K., Piscitello, J., Robertson, E. L., & Pelham Jr, W. E. (2024). Reconceptualizing the approach to supporting students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school settings. Journal of School Psychology, 104, 101309.

Fabiano, G. A., & Pyle, K. (2019). Best practices in school mental health for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A framework for intervention. School Mental Health, 11, 72-91.

Fabiano, G. A., Schatz, N. K., Aloe, A. M., Pelham Jr, W. E., Smyth, A. C., Zhao, X., … & Coxe, S. (2021). Comprehensive meta-analysis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder psychosocial treatments investigated within between group studies. Review of Educational Research, 91(5), 718-760.

Iznardo, M., Rogers, M. A., Volpe, R. J., Labelle, P. R., & Robaey, P. (2020). The effectiveness of daily behavior report cards for children with ADHD: A meta-analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(12), 1623-1636.

Mandalawitz, M. (2016). Special education after 40 years: What lies ahead. Policy priorities: An information brief from ACSD, 22(1), 1-7.

Pelham Jr, W. E., Fabiano, G. A., Waxmonsky, J. G., Greiner, A. R., Gnagy, E. M., Pelham III, W. E., … & Murphy, S. A. (2016). Treatment sequencing for childhood ADHD: A multiple-randomization study of adaptive medication and behavioral interventions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(4), 396-415.

Pyle, K., & Fabiano, G. A. (2017). Daily report card intervention and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of single-case studies. Exceptional Children, 83(4), 378-395.

Sibley, M. H., Graziano, P. A., Kuriyan, A. B., Coxe, S., Pelham, W. E., Rodriguez, L., … & Ward, A. (2016). Parent–teen behavior therapy+ motivational interviewing for adolescents with ADHD. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 84(8), 699.

Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (2009). Responsiveness-to-intervention and school-wide positive behavior supports: Integration of multi-tiered system approaches. Exceptionality, 17(4), 223-237.

Thome, J., & Jacobs, K. A. (2004). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in a 19th century children’s book. European Psychiatry, 19(5), 303-306.

Vujnovic, R. K., Holdaway, A. S., Owens, J. S., & Fabiano, G. A. (2014). Response to intervention for youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Incorporating an evidence-based intervention within a multi-tiered framework. Handbook of school mental health: Research, training, practice, and policy, 399-411.