APSARD Newsletter August 2025

The APSARD August 2025 Newsletter is now available! Click the button below to access.

APSARD Newsletter July 2025

The APSARD July 2025 Newsletter is now available! Click the button below to access.

Important Update: Department of Justice, CDC, and the Vital Role of APSARD

On June 13th, 2024, the US Department of Justice announced a federal health care fraud indictment against a large subscription-based telehealth company that provides attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) treatment to approximately 30,000-50,000 patients across the United States.

As per the US Department of Justice: “Ruthia He, the founder and CEO of Done Global Inc., was arrested in Los Angeles and David Brody, the clinical president of Done Health P.C., was arrested in San Rafael, California” for allegedly “developing and carrying out a $100 million scheme to defraud taxpayers and provide easy access to Adderall and other stimulants for no legitimate medical purpose.” As alleged in the indictment, “the defendants provided easy access to Adderall and other stimulants by exploiting telemedicine and spending millions on deceptive advertisements on social media. They generated over $100 million in revenue by arranging for the prescription of over 40 million pills.“

At the same time, the CDC issued the statement “Disrupted Access to Prescription Stimulant Medications Could Increase Risk of Injury and Overdose,“ which discusses the need for ongoing access to care and the potential disruption to as many as 30,000-50,000 patients ages 18 years and older across all 50 US states.

Within hours, the CDC hosted a meeting of the “ADHD Partners” to discuss these issues and the impact on the communities affected by ADHD. This meeting included Stephen Faraone from the World Federation for ADHD, CHADD leadership, the president of ADDA, ADHD coaches, other affiliated organizations, and me, from APSARD.

The overarching theme of this meeting was the need for holistic ADHD care, the pivotal role of APSARD and our affiliated ADHD organizations in decreasing stigma and improving equitable delivery of education and ADHD care.

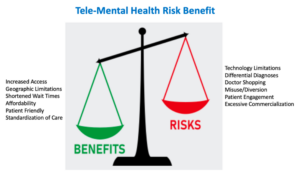

I would like to share a resource which was just E-published in CNS Spectrums, ahead of print last week, which utilizes an “Expert Consensus Statement” on the strengths and limitations of telemedicine for ADHD management and care.

All in all, these updates highlight the pivotal role of APSARD as the leading voice for implementing ADHD science, education, and advocacy for individuals with ADHD.

Appreciatively,

Greg Mattingly MD

President, American Society for ADHD and Related Disorders

Supporting Links:

Disrupted Access to Prescription Stimulant Medications Could Increase Risk of Injury and Overdose

Expert Consensus Statement for Telepsychiatry and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

NYT on Why Primary Care is in Need of Adult ADHD Guidelines

In this issue of Psychiatric Annals, we will present four articles summarizing issues in the development of United States (US) guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The American Professional Society of ADHD (APSARD) is currently in the process of developing such guidelines, which will be the first such recommendations for US clinicians treating adults with the disorder. Of note, there are multiple US guidelines for childhood ADHD, including those from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Multiple international organizations have developed guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD, including adult ADHD, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE; United Kingdom) and the Australian ADHD Professionals Association (AADPA). These guidelines outside the US particularly highlight the need for guidelines for adults in the US. Furthermore, such guidelines are important for both patients and clinicians as: (1) adult ADHD is often undiagnosed and untreated, at significant cost to the patient and to society; and (2) the guidelines will provide the latest evidence available to clinicians caring for patients with adult ADHD so that they and their patients can make the most informed decisions.

This issue starts with an article by Dr. Deepti Anbarasan and colleagues that reviews the development of quality measures for adult ADHD as a step along the way toward creating guidelines. Dr. David Goodman and Dr. Greg Mattingly then discuss the process of guideline development in the second article. The third article, by Dr. Thomas J. Spencer and colleagues, describes the process of conflict-of-interest management in the development of adult ADHD guidelines. The issue concludes with an article from Dr. Ann Childress and colleagues on the importance of the development of US guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD.

Watch the teaser video to learn more: NYT article 052024 teaser video.mp4

Read the full statement:

https://journals.healio.com/doi/10.3928/00485713-20230911-06

Medscape Features APSARD in the first US Adult ADHD Guidelines

The first ever U.S. clinical guidelines to diagnose and treat adult ADHD are expected to be released this fall. The guidelines are being developed by the American Professional Society of ADHD and Related Disorders (APSARD) due to a lack of existing standards and to improve accuracy of diagnosis and treatment. Experts believe the guidelines will help clinicians, especially primary care physicians, better diagnose and treat adult ADHD, and dispel myths surrounding the disorder.

For more details on the reasons behind the guideline development and the challenges of diagnosing adult ADHD, read the full article here: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/first-us-adult-adhd-guidelines-finally-way-2024a10006yf?form=fpf