Feb 14, 2016 | Research Updates

ADHD and Bipolar Disorder in Children

Joseph L. Biederman, MD

Joseph L. Biederman, MD

Over the last twenty years, since the 1990’s, there has been an increasing awareness in pediatric psychiatry that a sizable number of children, probably around one percent, have Bipolar illness. This is also supported by the fact that roughly seventy percent of adults with Bipolar illness start their illness in childhood and adolescence. We face a real problem that somewhere about one percent of children may be affected.

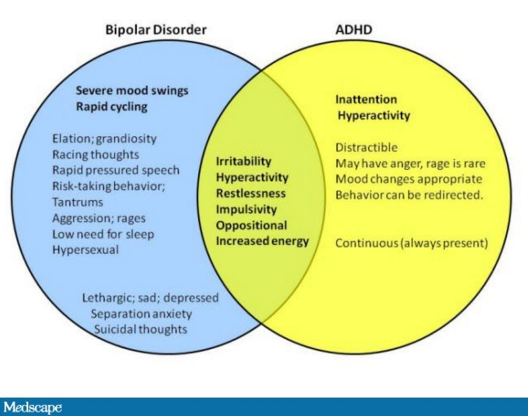

The problem in the field of ADHD and Bipolar illness is that about eighty percent of children with Bipolar illness also have ADHD. It’s not in reverse. The rate of Bipolar illness in children with ADHD is around twenty percent. The overlap is quite substantial, but particularly very, very high in children with Bipolar illness.

The reason this is important is because ADHD and Bipolar in children may share some symptoms, but they require very different treatments. The treatments that we use for ADHD can make worse the symptoms of bipolarity. Particularly if we use medicines like stimulants, or medicines like anti-depressants.

So these things are very consequential to the well-being of the child. Children with Bipolar illness frequently are violent, aggressive, and can be out of control. Very often they are so out of control that they need to be hospitalized. They become dangerous to self or others. So the differential diagnosis of ADHD from Bipolar illness has enormous clinical and therapeutic consequences.

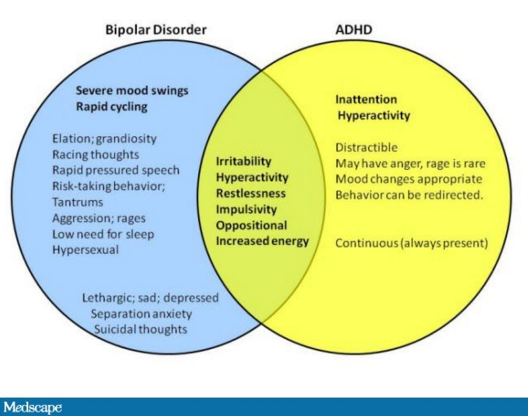

There are shared symptoms in common between ADHD and Bipolar Disorder, but they are different. Hyperactivity and agitation are not exactly the same. Hyperactive children move a lot, but they are not in an agitated state. Children with ADHD tend to talk a lot, but children with Bipolar illness talk so rapidly that sometimes they cannot be understandable.

But the major differentiation is in the abnormal mood. There is nothing in the defining features of ADHD that speak to abnormal mood. Bipolar children have very, very dysregulated mood. They frequently have the combination of aggression, manic symptoms, and depression all at the same time.

It’s a very complicated clinical picture that is usually known as mixed mania. Children with mania, more often than not, tend to be irritable, violent, and aggressive, not euphoric. The children present usually at a very young age, usually with symptoms of dyscontrol, and violence. Very often the symptoms present at home for a long time, before they spread to the school. Because when the symptoms emerge in the school, the child becomes unmanageable and usually is brought to the emergency room.

Despite the fact that some symptoms overlap, there are very, very important differentiating features between ADHD and Bipolarity. Remember I said before that eighty percent of children with Bipolar illness also have ADHD. The ADHD that they have is going to be very severe. But they also have mood dysregulation, irritability, and sometimes violent behaviors.

It is very important for clinicians and parents to learn how to distinguish ADHD from Bipolar Disorder, and treat each appropriately, particularly because of their high comorbidity. ADHD and Bipolar in adults can be similarly challenging, but here we have the maturity of adults who can better describe their symptoms.

Feb 8, 2016 | Research Updates

ADHD Genes Found

Stephen V. Faraone, PhD

For many years, ADHD scientists have been searching for genes that pre-dispose people to having ADHD, a very difficult investigation. It turns out that the solution to the problem of finding genes was in getting large enough samples, so that we had enough statistical power to actually find these genes. What has been created is an international consortium consisting of over 100 people from 14 countries and five continents who are studying the genetics of ADHD. We pooled our data into a very, very large genome-wide association study, then we studied the entire human genome, looking for genes or, I should say, DNA variants.

This is the DNA that puts people at risk for having ADHD. Right now we have about 17,000 ADHD people in this big experiment, along with 95,000 controls. It’s really the largest experiment study in ADHD ever to have been done. What’s really exciting about this in 2016 is that, finally, after many years of doing these genome-wide studies, we can finally say for certain that we have detected loci on these genomes that are what we call genome-wide significant, meaning that we’re very sure that they are pointing to genes that are associated with ADHD. We think we have between five and eight genes that we can be sure about. We’re actually finalizing an analysis. I presented the final results at the January 2016 annual meeting of APSARD, the American Professional Society of ADHD and Related Disorders.

So far, the genes that we’ve discovered are quite interesting, because they’re pointing to novel pathways that haven’t been considered before. For example, everybody knows about the Dopamine system in ADHD and the Norepinephrine system in ADHD. These are well-known biological pathways that have been located by the treatments for the disorder. We’re now locating biological paths which, for example, are involved in synaptic plasticity in the development of the brain. These are genes that are involved both very early on in the brain during development, from the fetal stage up through young adulthood. They are also involved in learning and memory in the remodeling of synapses.

We hope, in the long run, that discovering these new genes and new biological pathways will give us new insights into how medications might be developed to target very specific problems that will occur in the ADHD brain. These are very exciting days for the people who have studied the genetics of ADHD. More importantly, these discoveries will bring exciting new treatments to ADHD patients, their loved ones, and medical professionals.

Feb 4, 2016 | Research Updates

How ADHD Grew Up as Kids Grew into ADHD Adults

(Editors’s Note: This text comes from transcription of an extensive interview on November 23, 2015 with Ronald C. Kessler, PhD.)

(Editors’s Note: This text comes from transcription of an extensive interview on November 23, 2015 with Ronald C. Kessler, PhD.)

There’s a lot of evidence to show that the structure of ADHD changes from childhood to adulthood. For many years there was a widespread belief that ADHD kind of disappeared, people matured out of ADHD as they got into adulthood. We know now that’s not the case, but as we learn more and more about people who have ADHD as they age, we realize that what seemed to be that “ADHD disappearing” was really a transforming. The kinds of symptoms that people have change, so the hyperactive and impulsive symptoms become less prominent, the inattentive symptoms become more prominent, and also we’re coming to understand now that they’ve become more differentiated. It’s really the symptoms become more of a spectrum of executive dysfunction than just inattentiveness.

There’s also some thinking that there might be another dimension that becomes important, and it’s not just the cognitive part of the executive dysfunction, but some kind of emotional dyscontrol that looks somewhat different from hyperactivity or impulsivity in childhood. We’re interested in looking into that as a way of helping to refine the ADHD diagnostic criteria. As you in know DSM-5 has just been put into place in May, 2013. We looked at the full set of adult ADHD symptoms in the DSM-5, which is the 9 AD and the 9 HD impulsive symptoms. This is in addition to about a roughly equal number of other symptoms that had been suggested by various experts as being indicative of adult ADHD that you don’t see in kids. Again, most of these problems were associated with things having to do with executive function, so trying to manage complex tasks and things that a person might do as an adult worker is different from what a 12-year old child has to deal with.

We also asked about emotional dyscontrol. When we analyzed that, we found a very consistent structure across three surveys. We found clear evidence of one dominant factor that was really not AD (attention deficit symptoms.) It was again, the AD symptoms plus this broader array of executive dysfunction symptoms; not being able to finish tasks on time and juggling multiple tasks, and the kind of things that you and I and other people in the modern world have to deal with all the time.

We found four factors in adult ADHD patients: attention deficit, hyperactivity, impulsivity, emotional dyscontrol. All four of those were very strongly correlated in having a diagnosis leading to DSM-5 ADHD criteria. So we find that these factors are important, but as it turns out, the emotional dyscontrol measure, and the broader executive functioning measures that are not part of DSM-5 have associations with the diagnosis equally as strong as the symptoms that are part of DSM-5. So it’s very clear that the symptoms that are used right now in DSM-5 are really just a subset of a broader set of symptoms in the general population. That’s the first thing we found.

Then we’ve done some other interesting things based on that, looking at the profiles of people, and looking at the kinds of symptoms that seem to be dominant. The question is, is there any evidence to suggest that there is a broader spectrum of ADHD where people who don’t quite make DSM criteria had a large set of other items that should be in the same spectrum, but have been missed then. That’s the basic idea here.

We have DSM-5, which is like the physician’s desk manual for what is classified as ADHD and what is not ADHD in the field of mental disorders. New associations are being found. So what do practitioners do with that before DSM-6 comes out? How does this spread into the population of practitioners who are trying to correctly diagnose people?

One big purpose of this is forward thinking for DSM-6, which is now quite a ways off since we just started with DSM-5, but it’s important to get straight what the nature of the beast is if you’re trying to get better diagnoses. So we hope that over the next few years we will be looking at the data on the structure of ADHD to be the foundation for deeper studies to help us flesh out sub-types that are more meaningful in adulthood than in childhood. But for the “right now” part, what we’re finding is that even when a person meets current criteria for adult ADHD, the things that are the symptoms in DSM-5 might not be the presenting complaints!

One big purpose of this is forward thinking for DSM-6, which is now quite a ways off since we just started with DSM-5, but it’s important to get straight what the nature of the beast is if you’re trying to get better diagnoses. So we hope that over the next few years we will be looking at the data on the structure of ADHD to be the foundation for deeper studies to help us flesh out sub-types that are more meaningful in adulthood than in childhood. But for the “right now” part, what we’re finding is that even when a person meets current criteria for adult ADHD, the things that are the symptoms in DSM-5 might not be the presenting complaints!

Patients don’t come in to a doctor and say “Gee, I have a problem with things that are half impulsive, and half hyperactive.” Further, the aspects of inattention are very often kid-oriented and do not necessarily present as a problem for adults. It might be that for the doctor, it’s easier to pick up on the syndrome by asking about things that are not current in DSM-5. In terms of screening, the ability to find people who have a problem who don’t realize it yet, get them the treatment that could be helpful and improve the quality of life could be improved by us having a better understanding of what the real life problem is. Because of this, one of the spin-offs of this analysis is that a group of us are working on a revision of the ASRS Screener (ASRS V1.1, the current six question ADHD screener used by clinicians to screen for ADHD: Adult Self-Report Scale) that broadens the set of questions to include executive dysfunction, to see if there is a more diagnostic set of questions that could help us identify ADHD in adults. Then a group of us as well are studying the structural aspect of ADHD to see in clinical research studies if we should be probing a little bit more deeply for sub-types of ADHD where it might make sense to think of differential treatment response, or a treatment response to executive dysfunction in new ways that we haven’t used before.

The most notable is that the emotional dyscontrol set of symptoms don’t seem to be as distinct from the executive dysfunction problems, the way AD and HD are in childhood. It turns out that those emotional characteristics are more prominent in adulthood than we had previously thought when we were looking only at hyperactivity and impulsivity. We have had this conception that ADHD adults are just like tall kids; they have this AD part and they have this HD part. We’ve always known that AD is more prominent, but we now know it’s broader too. It’s really not AD, it’s executive dysfunction, and that’s sort of a richer, more variegated kind of problem.

Instead of it being just hyperactive and impulsive, it’s really hyperactive and impulsive and emotional dyscontrol, where you don’t see so much hyperactivity or impulsivity in adults but rather a more subtle kind of emotional dyscontrol. There are a lot of people as adults who have a combined type of ADHD, as opposed to a pure executive dysfunction problem. But you don’t see the combined aspect of it if all you do is focus on the impulsivity and hyperactivity. Neither of those are so obvious in adults, and you miss the fact there are these more subtle, emotional dyscontrol pieces if you are not looking for them using DSM-5 criteria.

ADHD was originally described in the early 1900’s, and here we are 100 years later, underlining how new this science is and our understandings are. It’s not uncommon to see definitions get carved in stone. There are many medical conditions that are not terribly difficult to study, if you look at them, but they just never get looked at because of pre-conceptions. For so many years there was this notion that ADHD was a disorder of childhood that that was the end of it. We never looked at adults because of preconceived notions. We’re now at the point where young adults are coming back to their old pediatricians and saying, “Hey, Doc, I still need some of that medication.”

As ADHD children have grown, we’ve started seeing this adult ADHD coming on. We’re now looking more closely into a rich, complex, and highly co-morbid condition that really makes a difference to people’s lives. We’ve known for quite some time that having ADHD as a kid is a predictor of other kinds of emotional problems in adulthood, depression and anxiety disorders, substance use disorders and so forth. We’re now coming to realize that it’s also a risk factor for this broader and subtler ADHD variant that we hadn’t recognized until recently, and then once we see it more clearly than we have in the past, it could well be that new treatment options present themselves that we haven’t appreciated before. That of course is the holy grail for us moving forward in understanding the full life spectrum of ADHD.

Jan 28, 2016 | Research Updates

ADHD and Brain Imaging – Improvements for Diagnosis and Care

I have collected neuro-imaging data over the years on how the brain processes opportunities to respond to rewards as well as notification of having received awards, and also the brain activation and response to the threat of penalties such as going for too much reward, when you should stop earlier. I am interested in how these brain signatures can relate to a couple of things.

I have collected neuro-imaging data over the years on how the brain processes opportunities to respond to rewards as well as notification of having received awards, and also the brain activation and response to the threat of penalties such as going for too much reward, when you should stop earlier. I am interested in how these brain signatures can relate to a couple of things.

First of all they may address different theories about what makes the addictive brain different. For example a theory holds that there is a reward deficiency in people who are addictive because of genetic characteristics, and/or from chronic use of substances use such as alcohol. The addictive person’s brain is relatively unresponsive to non-drug rewards. Another theory is more of an impulsivity theory that distinguishes people who get into drugs, and especially who lose control over substance use once they start, as impulsive. They’re characterized either by an exaggerated pursuit of rewards generally or some combination of that with an insufficient frontal cortex control over behavior. My work has been in adolescents and adult participants.

I would say on the whole my data are consistent with more of an impulsivity hypothesis but I would certainly welcome other clinicians and researchers to draw their own conclusions.

This work is very relevant to ADHD. We are trying to move away from diagnostic nosologies (classifications of diseases) and more toward a focus on circuit-level abnormalities; more focus on phenotypic abnormalities. There is a long pedigree of various papers in the literature, talking about the comorbidity between ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder, or between conduct disorder and so forth. That approach may become a bit outmoded as this circuit level approach becomes more in vogue.

One thing that is under-appreciated is that the brain is connected to itself across regions. The population of those with ADHD is distinguished by a separate connectivity pattern. If a patient presents with a more emotional-reactive or hot profile, whether you call it ADHD, emotional defiance, OCD, or whatever, he or she is at particular risk for substance abuse. Given the already published literature, I would contend having emotional aberrations alone is a risk factor for addiction.

Our ability now to measure brain patterns and connectivity will provide improved tools for diagnosing and treating disorders, emotional disturbances, risks for addiction, as well as developing reward structures that work, compared with the more classic labeling that we have relied on until now.

Jan 21, 2016 | Research Updates

ADHD and SUD

Brooke Molina, MD

I conduct research on the connection between ADHD and substance abuse. My research started about 20 years ago when researchers began to be interested in a possible link between these two problems. As we started to dig into it, we discovered that indeed there is a connection but what remains somewhat complicated is the extent to which there is a connection. So, just how much are these children at risk for which substances; alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes. When they are at risk, why? I’ll be talking about that.

I am asked if this applies to adults, and absolutely, it applies to adults. Much of our research has actually been following these children into adult to understand how long this risk lasts. Some folks have the apparent risk at different stages in their lives. Depending on how you study the question, it shows up differently at different ages. That’s the developmental component to my research.

As a result of part of our research, some people were surprised that we found that the most common treatment for ADHD, stimulant medication, did not have a clear and strong signal for preventing substance abuse. Some studies are showing that it helps. Some studies are not showing anything. The good news is that it doesn’t appear to be visibly be harming children or to be escalating their risk for abuse. In other words, we’re not seeing that stimulant medications spur on the use of drugs or alcohol, and that’s good news.

An important question arises when one considers the risk for substance misuse in teenagers vs. adults. Our research has focused quite a bit on the developmental issues here because substance abuse changes as people age. It starts when teenagers are young but it doesn’t rapidly jump to an addiction or substance abuse. If you try to measure it that way, you might miss it. Substance abuse looks a little different depending on the age of interest. We are working hard to understand what that looks like at the different ages and what are the different factors that lead to this risk at the different ages? We think that might have important implications for prevention and for treatment.

Jan 14, 2016 | Research Updates

ADHD in Adults Over the Age of 50

There’s a new topic in ADHD, and it’s likely to be the next clinical frontier, and that is ADHD in adults over the age of 50. We never truly believed that ADHD stopped when the pediatrician discharged you, and it doesn’t stop when you get your AARP card or your Medicare card. We need to follow these people into adulthood. Now, many of these people have really never been diagnosed, having been raised in the 1950s and 60s. It really is quite a challenge for clinicians to identify ADHD in the older population. I think that it’s important for the clinician to have ADHD in mind when they’re doing their psychiatric evaluation. Often ADHD is missed because it’s simply not considered in the evaluation. ADHD in adults starts in childhood. The symptoms are chronic and relatively unchanging, and cause impairments over time. In the later years of adulthood, making the diagnosis gets more complicated because of age related cognitive decline. Although cross-sectionally it might look like it’s just age related, if you don’t go back and take the history, you miss the fact that this person has had chronic inattention, distractibility, disorganization, for virtually their whole life. That is the challenge to making the diagnosis. Does ADHD present in ways that are unique from aging? Not necessarily. The inattention is still a function of the disorder. They’re forgetful, they misplace things, they spend a lot of time looking for things, but at this age, when you have multiple responsibilities now with children, or grandchildren, and family, and managing finances and career, things that previously would have been relatively straightforward for an average adult become problematic. That is, paying bills on time, managing finances, remembering what bills you paid, what bills you didn’t pay, making return phone calls, and life just gets too complicated and burdensome. This leads to an increase in the amount of anxiety and depression that people have. We’re often presented with anxiety, substance abuse, depression, and other concomitant psychiatric disorders. Again, the clinician needs to know this exists in order to screen and ask the relevant questions. That’s really what our program is going to be at APSARD, to heighten the awareness for clinicians. It is often the case that adults are getting diagnosed for the first time in midlife, because if you were raised in the 1950’s and 60’s, these were bad, lazy kids who never got diagnosed. Now what happens for the later adults is, they see their grandchild get diagnosed, and then their own child, 35, turns to mom and dad and says, “You know, you guys look like you were this way my whole life. You always ran late, you didn’t pick me up on time, and we were always scattered and looking for stuff when we went on vacations. Maybe you should get evaluated.” I think it’s a new frontier because there are very few studies that look at ADHD in older adults. We just did a review that has been published before the meeting, and it’s a complete review of English published worldwide literature on ADHD over the age of 50. There’s a lot of good research out of the Amsterdam Group, but we’ve tried to put together all of this information to one article so that we can increase awareness and say what’s out there, and what the field needs to develop in the area of research and clinical skills. A press release for the review may be viewed here, for more information: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-in-adults-over-age-50-a-mistaken-and-overlooked-psychiatric-disorder-in-the-aging-population-300195082.html

Joseph L. Biederman, MD

Joseph L. Biederman, MD

(Editors’s Note: This text comes from transcription of an extensive interview on November 23, 2015 with Ronald C. Kessler, PhD.)

(Editors’s Note: This text comes from transcription of an extensive interview on November 23, 2015 with Ronald C. Kessler, PhD.) One big purpose of this is forward thinking for DSM-6, which is now quite a ways off since we just started with DSM-5, but it’s important to get straight what the nature of the beast is if you’re trying to get better diagnoses. So we hope that over the next few years we will be looking at the data on the structure of ADHD to be the foundation for deeper studies to help us flesh out sub-types that are more meaningful in adulthood than in childhood. But for the “right now” part, what we’re finding is that even when a person meets current criteria for adult ADHD, the things that are the symptoms in DSM-5 might not be the presenting complaints!

One big purpose of this is forward thinking for DSM-6, which is now quite a ways off since we just started with DSM-5, but it’s important to get straight what the nature of the beast is if you’re trying to get better diagnoses. So we hope that over the next few years we will be looking at the data on the structure of ADHD to be the foundation for deeper studies to help us flesh out sub-types that are more meaningful in adulthood than in childhood. But for the “right now” part, what we’re finding is that even when a person meets current criteria for adult ADHD, the things that are the symptoms in DSM-5 might not be the presenting complaints! I have collected neuro-imaging data over the years on how the brain processes opportunities to respond to rewards as well as notification of having received awards, and also the brain activation and response to the threat of penalties such as going for too much reward, when you should stop earlier. I am interested in how these brain signatures can relate to a couple of things.

I have collected neuro-imaging data over the years on how the brain processes opportunities to respond to rewards as well as notification of having received awards, and also the brain activation and response to the threat of penalties such as going for too much reward, when you should stop earlier. I am interested in how these brain signatures can relate to a couple of things.